confronting cost

I opened the door to see my best friend from childhood, Randall, chewing on a pen top, facing me in his baggy jeans. We hadn’t seen each other for nearly a decade. As kids our lives seemed like mirror images and we were inseparable skateboarding, biking, and playing basketball on our block of South Central Los Angeles. But something changed in middle school. In eighth grade, while I was worrying about which private high school would give me a scholarship, he was getting arrested for the first time.

Complaints from students about the way financing companies are handling student loans are eerily similar to the problems that frustrated mortgage-holders in the wake of the financial crisis, and cost some of them their homes, according to a government report.

In its second annual review of student-loan practices, the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, or CFPB, says loan servicers make it hard for borrowers to pay off their loans early and, unless recipients provide explicit instructions, divide up early or partial payments in ways that are the most expensive to consumers.

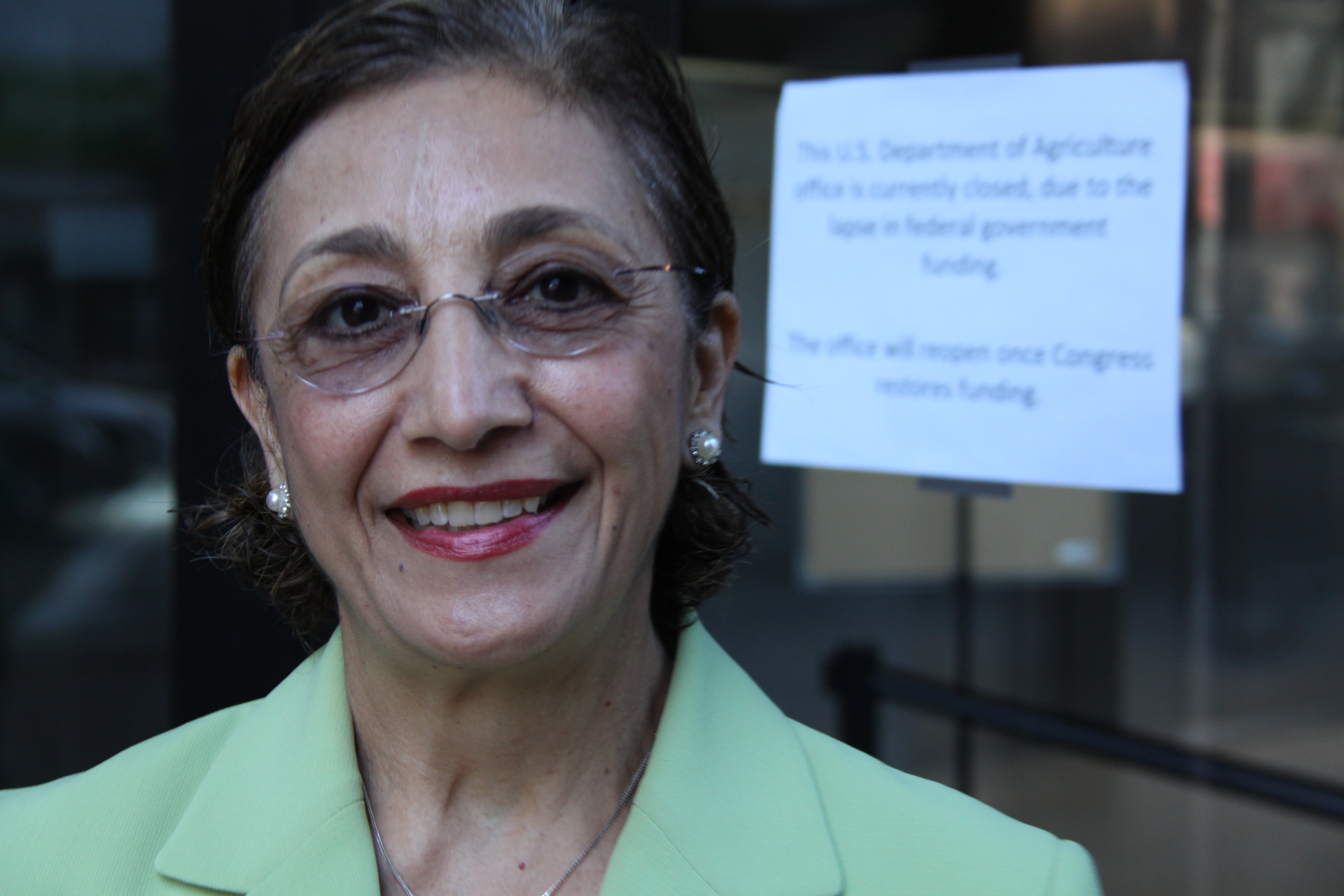

Since August, Westfield State University president Evan Dobelle has been under fire for expenditures he said he made while trying to boost the school’s financial support and brand.

Dobelle is the latest in an increasing number of college presidents to face scrutiny during this age of diminishing resources.

Former Massachusetts Education Secretary Paul Reville talked about the challenges facing college presidents on Greater Boston:

What you know determines where you go, according to a new book that sets out to determine why the smartest low-income students forgo the most selective colleges.

It’s not that poor kids aren’t as smart as rich ones, researcher Alexandra Walton Radford finds. Nor do top schools turn them down. In fact, she reports, low-income prospects have a big advantage in the admissions process at the most selective colleges.

The problem is that few of them apply, thanks to high school counselors and peers who know little about the admissions process, and parents who often know even less.

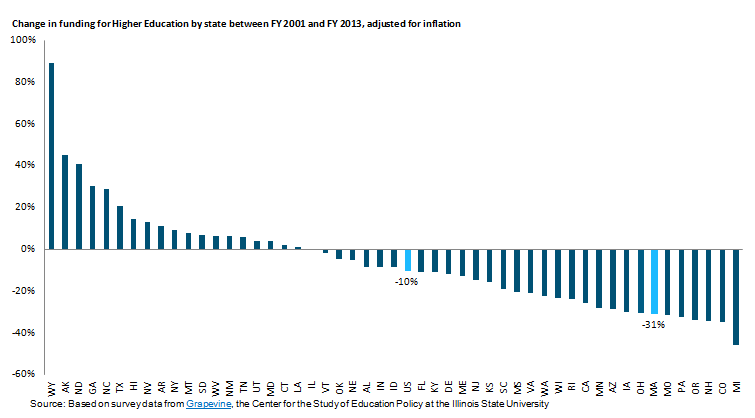

The recession may be over but its effects still linger at public colleges and universities.

The recession may be over but its effects still linger at public colleges and universities.

After facing declining revenue during the longest recession since the 1930s, many state governments continue to defund public institutions of higher learning.

A new report released this month by the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center finds state funding for public higher education in Massachusetts has fallen 25 percent since 2001.

They’ve been part of the higher education landscape since 1837 when Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Mass., opened its doors. But today, some women’s colleges are struggling to fill their seats.

They’ve been part of the higher education landscape since 1837 when Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Mass., opened its doors. But today, some women’s colleges are struggling to fill their seats.

Twice in the past six months, trustees at traditionally women-only schools have responded to that challenge by voting to go co-ed.

Today, there are only about 50 women’s colleges left in the U.S. That’s down from more than 250 in 1950. Twice in the past six months, trustees at traditionally women’s colleges have voted to go coed: Pennsylvania’s Wilson College in January and then right here in WGBH’s backyard Pine Manor College in July.

Today, there are only about 50 women’s colleges left in the U.S. That’s down from more than 250 in 1950. Twice in the past six months, trustees at traditionally women’s colleges have voted to go coed: Pennsylvania’s Wilson College in January and then right here in WGBH’s backyard Pine Manor College in July.

The National Institutes of Health, which provides the vast majority of higher education research funding, has suspended its operations, potentially undermining long-term college and university projects.

When the people with some of the greatest clout over the future of America’s universities and colleges convene in Austin, Texas, they’re not likely to attract very much attention.

They’re not athletics coaches, high-profile presidents, or marquee faculty who publish influential books. They’re not congressmen or legislators. They’re not rich donors or alumni.

They’re the representatives of philanthropic foundations, whose money — combined with the relative inertia of government and the higher-education establishment itself — has made them huge players in setting policy for the institutions that graduate the nation’s future workers and leaders.