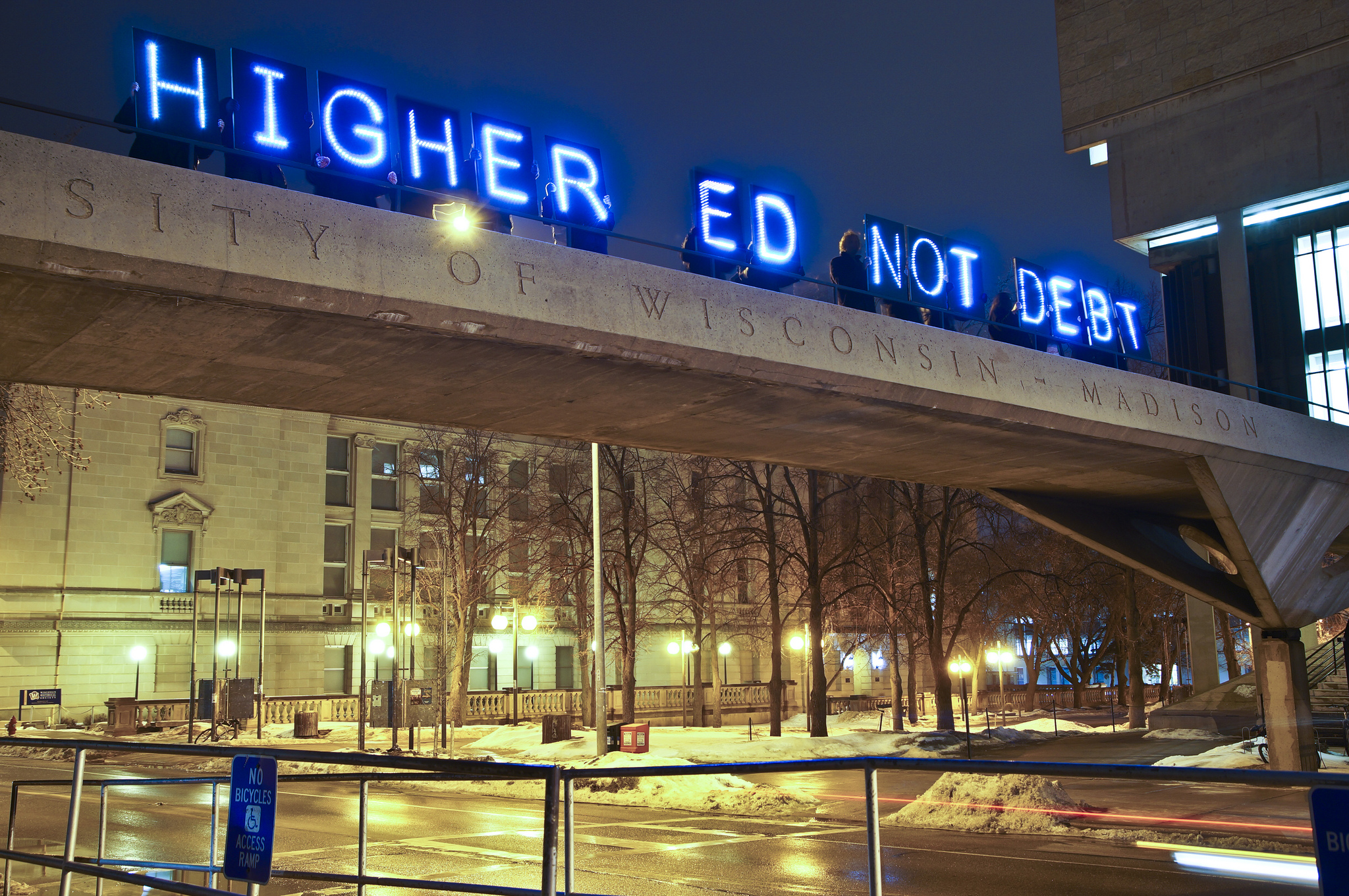

Students protest tuition hikes at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. (Flickr)

A new report out this week from the Brookings Institution looks at more than two decades of financial data, specifically how Americans are paying for higher education. The report finds the student debt crisis that we've all been hearing about isn't actually as bad as the public – and the media – often makes it out to be.

While the cost of college has increased dramatically, the Brookings report finds that monthly student loan payments have hovered around 4 percent of a borrowers’ monthly income for the past two decades.

Beth Akers is a fellow at the Brookings Institution. Akers studies student loan debt and financial aid and she says in 2010 only 7 percent of young households owed more than $50,000.

"What's not entirely consistent with the public narrative is that the burden of the debt hasn't seemed to increase dramatically over time as a lot of the media coverage would have you believe," Akers tells WGBH’s Kirk Carapezza.

Kirk sat down with Akers, who co-authored the report, to talk about the surprising findings.

Interview highlights:

Akers: Debt is increasing. The part that is not entirely consistent with the public narrative is that the debt burden hasn't seemed to increase dramatically overtime as a lot of the media coverage would have you believe.

Carapezza: So the impact of student loans may not be as dire as many commentators, including we in the media, may fear?

Akers: I think that’s right. One thing to keep in mind is that debt growing is not in itself a problem. Debt increases for a number of reasons; One because people are paying a higher price for college… but also because people are just investing more in higher education. A lot of the growth is coming from increases in graduate degree attainment. The innovation of the study was looking at the growth of debt in the context of the growth of income that has come along with it.

Carapezza: What was the most surprising finding in your research?

Akers: The fraction of monthly incomes spent on loan repayment has been flat or declining overtime.

Carapezza: What would you say to that psychology major who just graduated, can’t find a job, and is facing somewhere around $30,000 in debt?

Akers: The truth is, I really feel for this person. I think that we are not saying these problems are not real. What we are saying is that, on average and in the long run, these people are probably going to be okay.

Carapezza: Why do we have such conflicting reports?

Akers: The truth is that the narrative so far has not been completely informed by data, so a lot of what we are talking about is based on the anecdotes that have been covered in the media. The other thing is that the people who are talking about this, that is the reporters, policymakers, they come from a segment of society where people probably do have these large debts at a pretty high rate. So, without data to tell us what’s really happening in the broader economy, I don’t think it’s crazy that people came to the conclusion that debts are higher than they really are.

Carapezza: Is this debt in any way dragging down the US economy?

Akers: It could be. We are not ruling out this possibility. We’re just saying that it’s not the case that the severe hardship that we keep hearing about is widespread among borrowers.