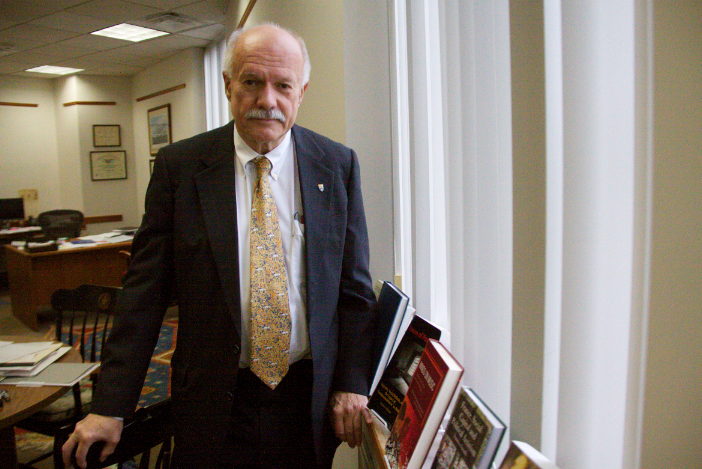

President David Flanagan of the University of Southern Maine in Portland. (Kirk Carapezza/WGBH).

Since the Great Recession, the amount of money states invest in public higher education has dropped dramatically. That, coupled with a steep drop in enrollment, has led some state university systems to cut faculty and academic programs altogether. In Maine, where Republican Paul LePage secured a second term as governor on Tuesday, those cuts are unlikely to be restored.

It’s early in the afternoon on the campus of the University of Southern Maine outside of Portland, and ten students file into their French seminar class.

It’s a class that won’t exist beyond this semester. That’s because overall enrollment at the public university is down - nearly 14 percent since 2009 - and there simply aren’t enough students who want to take the class. In fact, the entire major is being eliminated.

French Professor Nancy Erickson has taught at the school for 18 years. She said it's no secret that French had small enrollments, but she was still surprised by the decision to cut the major.

"Given the Franco-American, Franco-Canadian and Franco-African populations in Maine, it never occurred to me that French was an insignificant subject and one that didn’t need to be taught," said Erickson.

Erickson remembers when the school’s language department was so robust that it not only offered French, but also German, Russian, Spanish, Italian, Greek and Latin. Now, at the end of the year, she’ll lose her job and go on unemployment. And that’s left her frustrated.

"I mean we're all just expendable and interchangeable cogs instead of being people," said Erickson.

Like other public universities across the country, Maine is facing lower enrollments and a huge deficit. State funding for higher education has dried up, forcing public colleges and universities to increase tuition and fees. Since 2008, 29 states decreased their funding of public colleges and universities. Seven dropped public support by more than 20 percent.

Graphic courtesy of The Center for American Progress.

Administrators in Maine say cutting and consolidating programs is emotional but necessary.

"I knew that the University of Southern Maine was in a financially unsustainable position,” said University of Southern Maine's new president, David Flanagan.

Flanagan, a former energy executive, was brought in by the school's Board of Trustees to make these hard choices.

"It was going to be necessary to balance the budget in order to have any kind of future as a higher education institution," Flanagan explained.

Those hard choices included cutting four other majors in addition to French. Now, administrators are deciding, among other things, whether to merge philosophy, history and English into one department.

At a recent campus protest, senior Meaghan LaSala, 25, said she’s worried that faculty cuts will result in larger class sizes, diluting the quality of her affordable education.

"I really believe that if we put a pause on all this, and decided as a region and as a state that we want to invest in this institution that those numbers would turn around," said LaSala.

For LaSala, who enrolled at USM after working for a few years as an independent journalist in Portland, it’s important that this low-cost college get back on solid financial ground.

"I wasn't looking at a bunch of schools," LaSala said. "It occurred to me to go back to school because I saw what an incredible resource I had right here in my hometown."

She’s not unlike the students in USM's French seminar - the vet who just returned from Afghanistan and the high school students hoping to earn some college credit. They’re all looking to get ahead - to earn a college degree without taking on excessive debt.