Students in the fourth grade at an elementary school in Essen, Germany (Mallory Noe-Payne/WGBH).

In the final part of our series on German higher education, WGBH's On Campus reports on Germany’s tracking system, where kids are divided up by ability at a young age. The system seems to work well in Germany, but would face strong opposition in the United States.

At an elementary school in Essen, a city in northern Germany, students stream in from recess. They stuff boots into cubbies and hang up their jackets.

As this fourth grade class gets down to work, they begin on a lesson you wouldn’t find being taught in a classroom in the U.S. – the history of the bicycle. But in every other regard, things here seem the same. Students take all subjects with one teacher, all in the same classroom.

But next year that will end.

Each student will be placed into one of three different tracks: gymnasium, realschule, or hauptschule. Gymnasium is eight years of university-prep school. Realschule is only six years, and typically leads to an apprenticeship instead of college. Hauptschule is the lowest track, and is meant to serve slower learners.

Bela is one student in this classroom. He wants to be a deep-sea diver when he grows up, studying marine ecosystems and animals. To do that, he’ll have to go to university.

In the United States, 66 percent of high school graduates enroll in college. But in Germany, only a third of students do.

Germany is very selective about who gets to go to college because the state pays for every student to attend a public university and there are a limited number of spots.

In Essen and other cities and towns in Germany, students have the same teacher for their first four years of school. It’s that teacher who will ultimately decide what track is the best fit for a student.

Lis Vincenz is the principal here. She said this system puts a lot of pressure on teachers, who have to make these tough calls with anxious parents peering over their shoulders.

Lis Vincenz is the principal here. She said this system puts a lot of pressure on teachers, who have to make these tough calls with anxious parents peering over their shoulders.

“They just had their mid-term grades last week, and it only took three hours for the first parents to complain,” Vincenz explained. “Parents feel very pressured to have their kids be university-bound.”

Vincenz isn’t a big proponent of the tracking system and she would like to see students stay together for a longer period of time.

Vincenz once taught at a hauptschule, the lowest track. She questions whether full potential can be predicted so early, pointing out that students at hauptschules are disproportionately poor or children of immigrants.

“Any form of tracking is a form of discrimination really,” Vincenz said. “Even if you don't tell that to the children, they are feeling that they are not really wanted.”

Supporters of tracking point to Germany’s vocational system, where students who don’t go to college are given the opportunity to learn a trade. Graduates of vocational education are still able to earn good money, sometimes even more than college graduates.

Related: Stigmatized in America, 'Blue-Collar Aristocrats' Thrive in Germany

“I see the functionality in it, and I’m impressed by the society that results from it,” said Joshua Hallet, an American expat living in Germany.

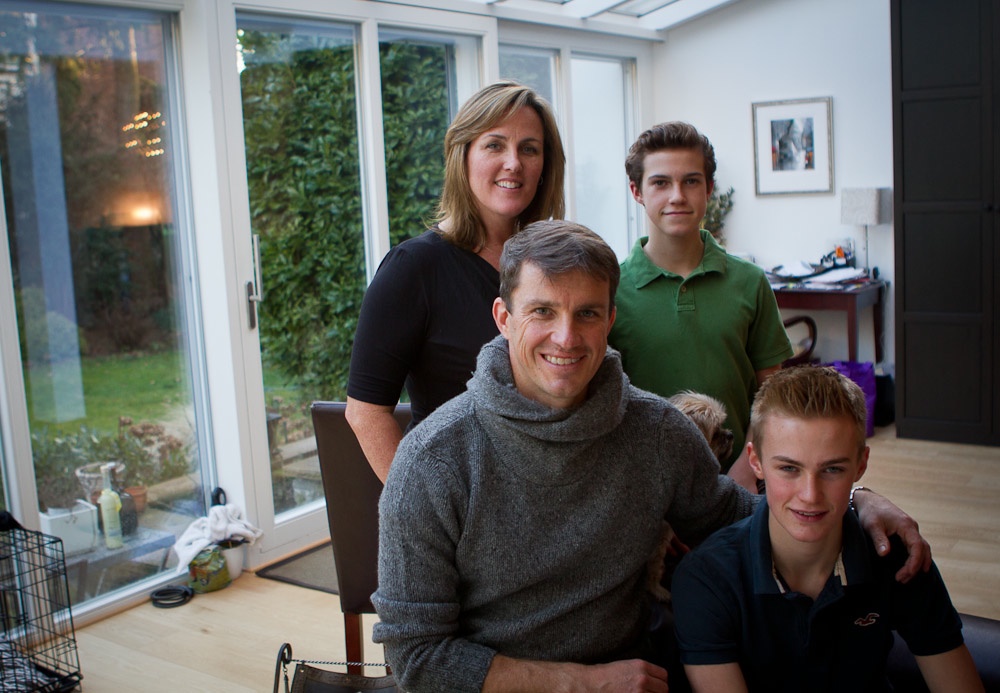

Hallett and his wife Wendy live in Dusseldorf, an affluent city north of Cologne. They have two teenage sons who are on the university track.

“If I look at [tracking] from an analytical standpoint, as opposed to, 'My child is involved in it,' what I see is a system that yields students who are normally falling through the cracks in the U.S., who drop out in 10th or 11th grade,” Hallet said. “Or who are part of the American youth who think they are going to the university because that's the only option to being a successful American.”

Wendy Hallett says she loves the tracking system. Her sons are high-achieving students, and she said they were always held back in American schools.

“For our kids to be pulled out and now be in a classroom of basically all gifted and talented kids, it's insane,” Wendy Hallett said. “They're taught at a level that they understand and where they can perform.”

The Hallett family is American, but have lived in Germany for three years. (Mallory Noe-Payne/WGBH).

Subject matter doesn’t necessarily differ from track to track, but the depth and pace of teaching does vary. And, said Joshua Hallett, Americans would be quick to call that unfair.

“The tracking system in Germany is so, for lack of a better word, un-American,” Hallett said. “It doesn't give you that golden ring to reach for. Americans are bred from an early age that nobody can tell you what to do, but you can do what you want.”

The irony is that the American comprehensive high school was partially a reaction to Germany’s tracking.

In the 1950s, former Harvard president James Bryant Conant served as an ambassador to Germany. He didn’t like the tracking system he saw there, so he came home and led a movement to reform American schools.

It took 30 years, but by the 1980s any type of tracking in the U.S. – even within high schools – was widely considered regressive and unjust.

In Germany, though, the system hasn't changed much in 60 years, even though parents like Anya Turner worry about the effect it's having on their children.

“My daughter is maybe not as focused as we want her to be sometimes. And having looked back at my education I can relate,” Turner said. “I would find it very sad for her path to be set after the fourth grade.

Turner's daughter is 9 years old and will be placed on track soon. If she isn’t recommended for gymnasium, the university track, Turner and her husband could decide to ignore the suggestion and send her there anyway. In the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, the government recently granted parents the right to make that choice.

However, ignoring a recommendation is still rare because, for all their misgivings, Germans still trust the system.

This is part four in our ongoing series that examines higher education in Germany, and compares it to the challenges we face here in the U.S.

To see the rest of the stories visit German Lessons: What the U.S. Can Learn About Education From Germany