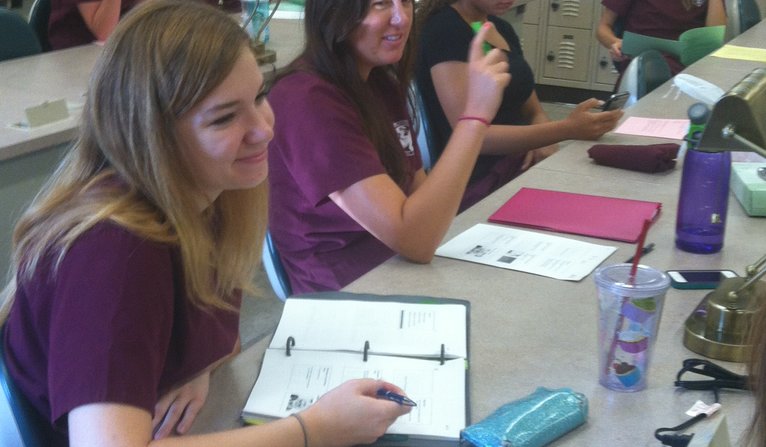

Students in a pediatric dentistry class at the University of Minnesota, including Niki Marinelli, say they don't always buy required textbooks for courses (Annie Baxter/Marketplace).

As families pack the 18-year-olds off for college right about now, they've hopefully confronted the cost of tuition, room and board, and health care. Then there's the cost of textbooks. One estimate figures the average is $600 for books and materials per year, another estimate runs twice that. Some students save money by renting or buying used textbooks. Others, given the cost, don't get the books at all.

______________________________________________________

On the last day of a pediatric dentistry course offered this summer at the University of Minnesota, adjunct assistant professor Jen Post asked her class a pointed question.

"For the purposes of planning for next year, I'm just wondering how many of you bought the book for this course," she asked. "Anyone?"

Not one aspiring dental hygienist raised a hand.

The $85 textbook was, technically speaking, optional. But Post says even when it was required in years past, few students bought it. They also didn't even try to rent or borrow it.

"Then they didn't know answers on exams. They didn't know where it was coming from," says Post.

Faculty at several other schools report similar problems. In a survey conducted last fall by the National Association of College Stores, nearly a third of students polled said they didn't buy or rent at least one item required for a class, often a textbook. And an equal share of students waited until after the start of school to buy anything.

"They want to make sure that whatever's required of them to purchase or rent or borrow from someone else, that they're going to be used," says Richard Hershman, vice president of government relations for the trade group.

Niki Marinelli, a senior in the dental hygiene program at the University of Minnesota, says she often just relies on study guides or will borrow a textbook from a friend to avoid buying books.

"Sometimes I see how I did on the first test and go from there. I see if I feel a book would've been helpful if I didn't do so well," she says. "Most of the time I'm okay. I'll go in if I have any questions."

Marinelli says loans cover the $10,000 she pays each semester in out-of-state tuition. But book costs come out of her own pocket. And she already works two jobs.

Rick Hess, director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, says professors need to be sensitive to textbook affordability. But he says it's shortsighted of students to spend thousands of dollars on tuition and then skimp on books.

"It's a case of students essentially seeming to think they're paying for the credential for the degree but they're not all that concerned about the learning that goes along with it," he says.

Jen Post is concerned about it. Post now filters the textbook content down to 50-minute powerpoint presentations, which are the basis of lectures and exams. It's the best way to ensure students get exposed to the information in the book. Post says if she didn't do this, her students would turn instead to Google and YouTube for answers to their homework assignments. And those answers are often wrong.

"They're just thinking everything's at their fingertips," she says, "When it might be in the book."

This story originally appeared on Marketplace Morning Report.