Chinese graduate of Boston University, Debra Zhang, walks to work down Boylston Street (Mallory Noe-Payne/WGBH).

It's eight in the morning, and Debra Zhang is heading to work. She grabs her keys and umbrella, slips on her shoes, and steps on to Boylston Street in Boston's Fenway neighborhood.

"I fell in love with the Charles River the first time I came. It was so great, so peaceful, and bright," Zhang said. "I love the city."

Zhang is from northeast China, and she earned her undergraduate degree there. But three years ago, the 25-year-old decided it was time to go abroad -- to study public relations at Boston University.

"And to improve language skills and meet people from diverse backgrounds; experience American education, talking to professors who are so experienced and awesome in knowledge," said Zhang.

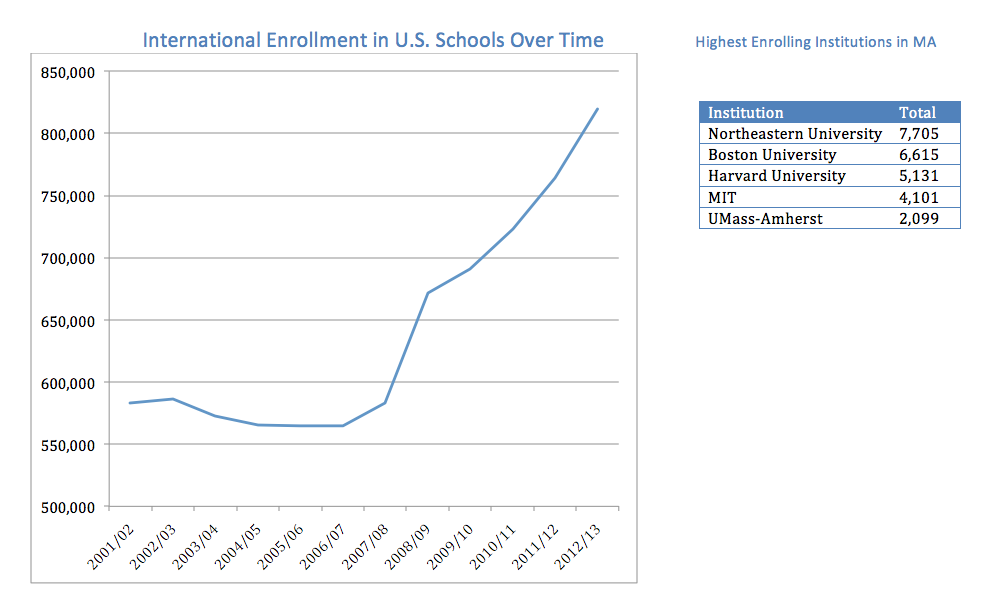

Today, more than 800,000 international students attend American colleges and universities, more than 46,000 of them in Massachusetts. Schools are expecting a spike this fall. This trend has implications both for international and domestic students.

International students don't qualify for financial aid in the U.S. and Zhang's immediate family couldn't afford the full $130,000 for her two-year master's degree. So other relatives picked up the tab.

"My aunt-in-law said, 'Well, just go ahead I will support you," Zhang said. "My mom also supported, almost all her savings."

Zhang isn't alone, the vast majority of international students are paying full-freight. Most in the U.S. come from India, South Korea and Saudi Arabia -- but above all, China.

Data from the Institute of International Education (Mallory Noe-Payne/WGBH).

"Essentially schools are doing more one-stop shopping in China, because it's easy," said Parke Muth, the former director of international admissions at the University of Virginia.

According to Muth, colleges and universities in the U.S. have become addicted to these full-paying international students.

“Many schools have priced themselves out of the market for income levels in the United States that can pay the full tuition,” said Muth.

And as schools accept more international students, there's the concern that middle-class Americans are being boxed out. Muth, who now runs his own admissions consulting firm, says that's simply not the case.

“In some ways, these international students who are full payers are helping to subsidize low-income students,” said Muth.

They are also helping subsidize our economy. Last year, international students contributed $24 billion dollars to the U.S. in tuition and living expenses.

But money is only one part of the equation. Muth says international students change the dynamics of a classroom and a campus.

"They bring incredible points of view that aren't often shared in class," Muth said. "They have experiences that are not only going to increase the level of discussion in classrooms but in the dormitories."

Kabrina Chang is a business professor at Boston University, where nearly a quarter of the students are international.

"The classes would not be nearly as rich," Chang said.

Chang agrees that diverse classes can create interesting conversation, but some non-native English speakers need prodding to raise their hand and comment in class.

"We come up with a plan, and it's usually, 'Okay Thursday in class I'm going to ask you these two questions so you prepare it, you know, get comfortable with it and know that I'm going to call on you," Chang said.

Chang goes out of her way to help students, making herself available during office hours and offering online forums as another way to get participation points.

"It seems to me they feel like they're really part of the group and part of the class," Chang said.

Inside a cafeteria on BU's campus three American students eat a quick lunch before class. When asked, they all agree that the international presence on campus is significant.

"I would say most of my classes, over half are international usually," said junior Julia Uchida.

"Also where we live, like on my floor last year at Warren Towers literally, I think half of my floor was international," jumped in junior Emma Olswing.

Gabby Fougner listed several countries represented in her dorm building: Turkey, India, China, Germany and Russia.

Junior Audrey Wood has had two international roommates since coming to Boston University.

"It's hard to totally befriend someone from a different culture because there's different culture cues that you might be missing," Wood said. "I don't know, I think we do get a huge benefit but maybe not the full benefit just yet. I don't think we've fully integrated."

Meanwhile, Boston University graduate Debra Zhang says she's made good friends since moving to Boston, but she still recalls times she didn't fully feel part of the group.

"I could feel, from professors, teammates when doing team projects, I felt their misunderstanding about our experience here," Zhang said. "They didn't know that we could contribute a lot in teamwork. It was understandable that they didn't want to cooperate with us. So yeah, it was sad."

Overall though, Zhang enjoyed her time in the U.S. She'd like to stay and work longer, but without job prospects she's decided to go back home to China.

In part two of our series, On Campus explores why many of the international students that study in the U.S. don't end up staying and working in America: