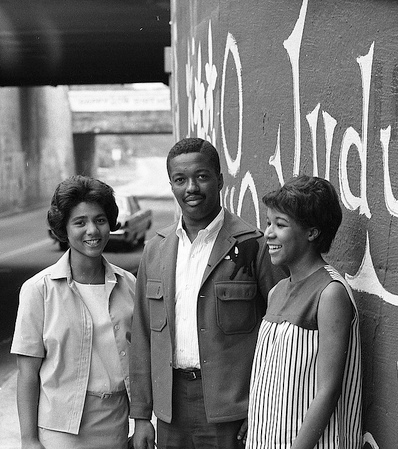

The first three African-American graduates of Duke University (Courtesy of Duke University Archives).

This Saturday marks the 60th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court ruling that paved the way for American schools to desegregate. Integration was a slow, and often violent, process that wasn't isolated to the American South.

In Boston, in the 1970's, a judge ordered the busing of children from one part of town to another to integrate public schools. Known today as the busing crisis, the court order set off a wave of protests.

This week, on Basic Black, panelists answered the question: What's the legacy of Brown? Discussion starts at minute 13:00. Below are some highlights from the conversation.

“In schools the (legacy of Brown) is less positive. In fact it’s very disheartening. If you look at our schools they’ve been resegregated, our urban schools have been resegregated. Something like three-quarters of African American children go to schools that are desegregated racially and in terms of poverty… This is personal to me because I’m a Brown baby, I benefitted from it… We know there was a high point of racial integration in the 70’s and 80’s and then it plummeted from there… I would say the legacy today is dim.”

- Kim McLarin, Writer in Residence at Emerson College

“The biggest problem, when we look at the data, is the idea of residential segregation. And how residential segregation further forces school segregation, people now want neighborhood schools. Busing is dead in the United States… Cities like Seattle and Boston are trying to do neighborhood schools. What we’re seeing with neighborhood schools…is high-income parents are being driven out. So residential segregation is a huge part of Brown’s legacy. We didn’t defeat residential segregation.”

- Peniel Joseph, Professor of History at Tufts University

“Brown was more than about getting black kids in schools with white kids… Segregation was a way of underfunding black schools… As long as the school were segregated they were going to be under-resourced, they were going to be under-funded, they were going to be second-tier schools.”

- Kenneth Mack, Lawrence Biele Professor at Harvard Law School