Credit: Monty Rakusen / Getty Images

*This piece was originally published on February 26th, 2021.*

Imagine a crime scene, and what it might take to solve the case. Do you think about dusting for fingerprints? DNA collection? According to Kate Winkler Dawson, author of “American Sherlock: Murder, Forensics, and the Birth of American CSI” and associate professor of journalism at the University of Texas at Austin, the man we can thank for that approach is Edward Oscar Heinrich. In the early 20th century, Heinrich took the world of forensics from guesswork, confession, and coercion to a place of science and nuanced evidence. While some of his experiments have been discredited in recent years as “junk science,” Heinrich’s impact can still be seen in the way many crime scenes are evaluated today.

Three Takeaways:

- Oscar Heinrich got his start working as a pharmacy tech to support his family after his father passed away. On that job, he learned a great deal about chemicals and compounds, but he also learned about human behavior, which became the foundation for his forensics career. Arthur Conan Doyle’s character Sherlock Holmes first surfaced in 1887, so the comparison was easy: two puzzle-solving men who used minute details, bits of overlooked evidence, and a dizzying amount of obscure knowledge to solve crimes. But Heinrich seemed to have a love-hate relationship with Holmes; he claimed that while Holmes used hunches, he did not.

- Heinrich’s expertise was sorely needed during this era of U.S. history. Prohibition had started a crimewave around the country, spawning criminal empires like Al Capone’s, and bringing crime up more than 80% from the decade before prohibition’s introduction. Heinrich had already worked with forensic methods like toxicology, ballistics, and handwriting analysis in the 1910s, but the police needed better tools and more educated officers. Heinrich started teaching criminology at UC Berkeley, and police forces across the country began sending their cops to his classes. Over the years, he taught thousands of officers, creating a new level of national competency among police forces when it came to crime scenes.

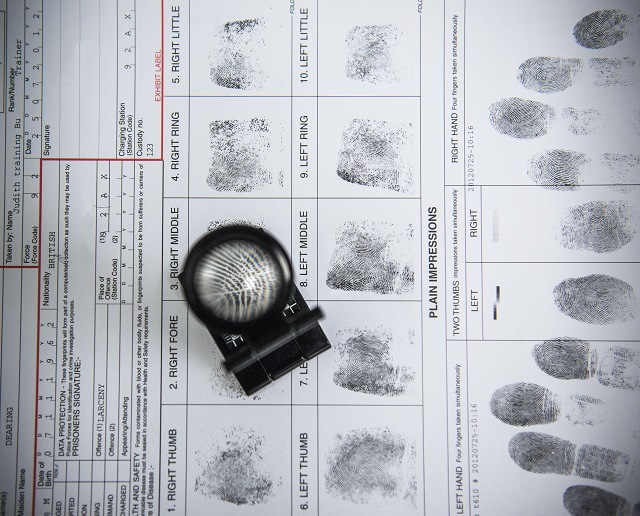

- Heinrich closed more than 2,000 criminal and civil cases over his career, and there are tools that he developed that are still used today. However, not everything stood the test of time. Some of his methods are now considered “junk science,” like analyzing bloodstain patterns or using lie detectors. Evidence that relies on “pattern matching,” such as bite marks, fingerprints, shoe prints, or recovered textile fibers, are open to the interpretation of the expert and aren't always reliable either. However, Dawson says Heinrich’s confidence in his methods and deductions was unwavering during his career.

More Reading:

- Kate Winkler Dawson has other books you can check out, including “Death In The Air” which focuses on the great, suffocating London Smog of 1952, and a serial killer who haunted the city at the same time.

- Plenty of “junk science” is no longer used as evidence in cases, but DNA evidence — often thought of as an infallible gold standard — might also be less reliable than we would like to think. Check out this Frontline piece about where DNA testing goes wrong, and see what one group is doing about wrongful convictions that have come from DNA evidence.

- Heinrich played a key role in the manslaughter trial of silent film star, Fatty Arbuckle. You can read more about the case that shook Hollywood here.