Credit: Boris SV / Getty Images

When figuring out how to tackle a problem, our instincts are almost always to add: we make to-do, not to-don’t lists after all. But just because humans have a harder time seeing subtraction as a viable solution — which can come in the form of tearing down buildings, dismantling barriers, and pruning old ideas — doesn’t make it any less useful of an approach.

Leidy Klotz is a professor of architecture, engineering, and business at the University of Virginia and the author of “Subtract: The Untapped Science of Less.” The idea of studying subtraction crystalized for Klotz when he and his son were trying to level a Lego bridge. By the time Klotz grabbed an extra Lego to even things out, his son had already solved the problem by removing one. Klotz now studies why we overlook subtracting as a way to improve things, including the various biological and cultural forces that push us towards more even when less would serve us better.

Three Takeaways:

- Our natural tendency to add rather than subtract stems, in part, from it being much harder to “demonstrate competence by subtracting,” Klotz explains. Monumental feats of architecture, like the Great Pyramids and Great Wall of China, stick in our minds because of their grand scale, and are integral to how towering civilizations demonstrated their superiority.

- Klotz and his collaborators have conducted thousands of experiments that present participants with the choice to add or subtract. In one, participants were presented with a bloated Washington D.C. itinerary containing too many tourist activities for anyone to feasibly enjoy in a day. When tasked with improving the “obviously overbooked” itinerary, specifically designed to trigger subtraction, participants still added more activities in the name of improvement.

- Divestment — the act of removing an investment, often for political reasons — is an example Klotz points to as a subtractive tool for change. Divestment from companies that traded or operated out of apartheid-era South Africa proved to be a highly effective anti-apartheid tactic, as institutions removed investments that were propping up a regime they were morally opposed to.

More Reading:

- Intrigued by the idea of subtracting? In a previous Innovation Hub episode, Cal Newport advocates for lessening our hyper-reliance on email. Listen to learn more about how our overstuffed inboxes might be hurting our work and personal lives.

- In 1989, an earthquake shook the World Series minutes before it was time to throw the first pitch, killing 63 people and causing billions in damage. This brief ESPN documentary digs into the disaster, which resulted in the eventual removal of a damaged double-decker concrete freeway.

- The approach college student Maya Lin took to designing the U.S.’s national Vietnam Veterans Memorial — stoically presenting the names of every soldier killed in the conflict on marble slabs that span on and on — was immediately controversial, though the monument is now widely acclaimed. Click here to learn more about why Lin viewed her approach, often characterized as minimalistic, as an honest way to commemorate the war’s fallen.

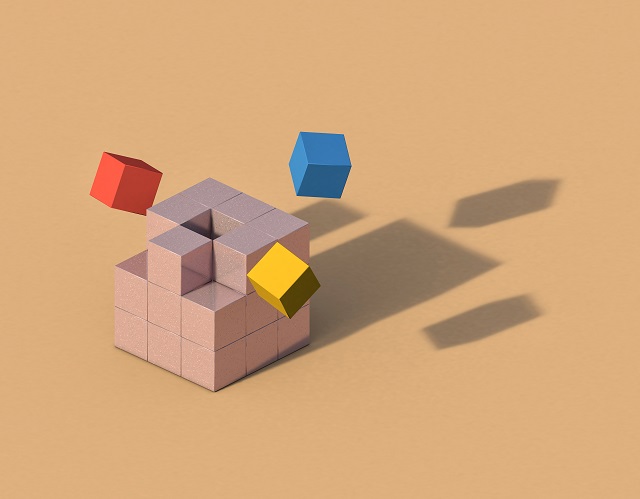

- Ready for a puzzle? This Washington Post article dives into one of Klotz’s other subtraction experiments, in which participants were presented with an asymmetrical image and asked to balance it in the simplest way possible. Half failed.