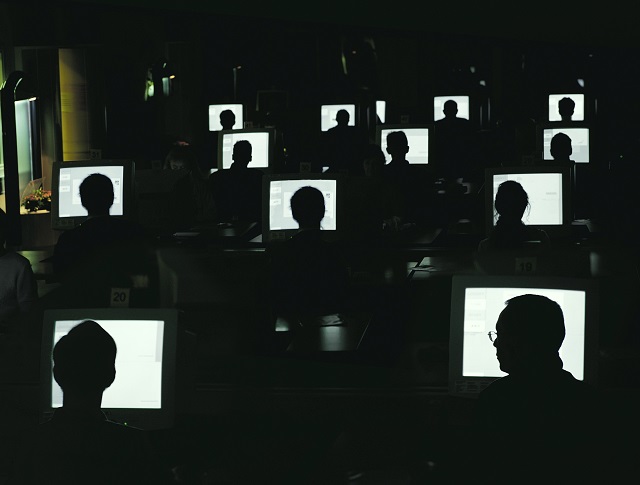

Credit: David Trood / Getty Images

Last April, states began to sporadically reopen after weeks of being shut down. Georgia was among the first to begin the process, while some states didn’t start lifting restrictions until June.

The uncoordinated reopening caused chaos, according to Sinan Aral, director of MIT’s Initiative on the Digital Economy. Why? Because Georgia pulled in hundreds of thousands of visitors from neighboring states - folks hoping to get a haircut or go bowling.

Aral was tracking Americans on social media, and it became clear to him that having uncoordinated coronavirus policies doesn’t make sense. As people watched their social feeds fill with images of people heading back outside, they stepped out too — even if their state wasn’t at the same phase.

Aral, author of “The Hype Machine: How Social Media Disrupts Our Elections, Our Economy, and Our Health — and How We Must Adapt,” has used social media as a tool to gain insight into everything from pandemic reopenings to protests and politics. And core to what he’s learned is that “social media is designed for our brains.” Humans have an intrinsic need to seek out and process social signals, he says — something we’ve used to our advantage throughout history. But the invention of social media? It’s “like throwing a lit match into a pool of gasoline,” he says. We can’t look away, no matter the cost.

Three Takeaways:

- Social media is immensely powerful, Aral says. The “tremendous leverage” it has to “influence opinions and behaviors in the physical world” can be captured for good or bad. How do we hang on to the good and scrap the bad? Aral says creating more competition could go a long way.

- There’s a strange dance between real people tweeting fake stuff and fake accounts amplifying those tweets. That was clear in 2014, when Russians used social media to reframe the annexation of Crimea as an “accession,” rather than a takeover, Aral says. This changed its perception on the ground and internationally, as diplomats struggled to decide whether or not to intervene.

- The Russian social media strategy in 2020 is “much more sophisticated” than it was in 2016, Aral says — and the U.S. intelligence community agrees. As platforms have cracked down on fake accounts, Russia has covertly encouraged U.S. citizens to “start and spread false propaganda and manipulative content.” Plus, they’ve moved their servers to U.S. soil, which makes them harder to find.

More Reading:

- In their recent study on mobility and social distancing during state reopenings, Aral and his co-authors scoured data from over 27 million mobile devices and 220 million Facebook users. They found that online behaviors in specific regions have a significant spillover effect that can change behavior thousands of miles away.

- Earlier this week, House lawmakers called for huge changes in antitrust laws to crack down on big tech monopolization, the culmination of an act proposed about a year ago. You can read the full report here, or head to this New York Times article for a more brief account. But this opinion piece in Wired claims break-ups wouldn’t actually change that much.

- Parents have long discussed the impact of technology on children. With the coronavirus making it harder than ever to distance kids from devices, because of remote learning, these conversations have taken on new urgency. This Vox article answers a few of our COVID-era concerns. But the bottom line is there are still a lot of unknowns about the long-term effects.