Biology professor Lloyd Matsumoto says he was at a department picnic at Rhode Island College when he first realized he might have a serious health problem.

A doctor at the picnic took one glance at his swollen legs, and told Matsumoto to get a check-up. He did, and found out a liver disease he’d been dealing with for decades had led to cirrhosis, and there were now cancerous tumors on his liver.

At 71, he needed a transplant.

Lloyd Matsumoto. Credit: Craig LeMoult

A lot of Matsumoto’s former students volunteered, but nobody was a good match for a living donation. So he went on the list to get a liver from a deceased donor.

Matsumoto was on the transplant list for a year and a half. As he waited, he got sicker and sicker. Jaundice yellowed his complexion and turned the whites of his eyes orange. And then, one of his doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston offered him an opportunity to join a clinical trial.

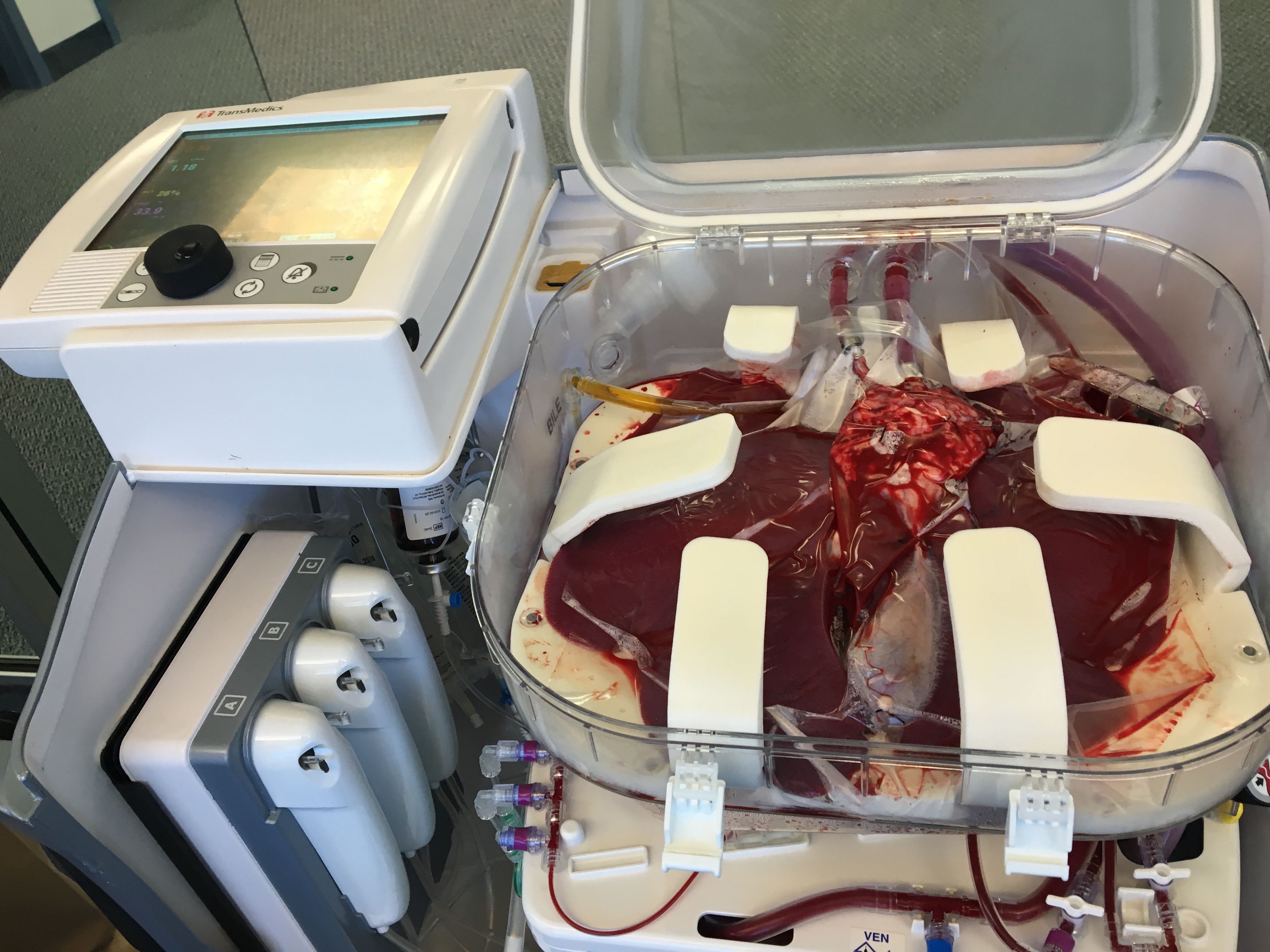

“She told me about this experiment about using a heating system to heat the liver before it got transplanted into me,” Matsumoto said. “And I replied: ‘Research? I’m a scientist. Hello... I’m going to do it.’"

The trial focused on what would happen to the donated liver right before the transplant.

Traditionally, organs are cooled down as quickly as possible once they’re removed, for the same reason you put a steak in the fridge: Doctors are trying to slow down the organ’s decay.

But some have begun to wonder if there’s a better way to do it.

When he was a surgical resident, Waleed Hassanein was told to go to a Virginia hospital to collect a heart from a donor who had just died - kind of like what you see on TV.

“Being the most junior member of the surgical team, I was in charge of bringing the igloo cooler and the preservation solutions,” he says.

As he looked at the cooler, Hassanein found himself asking: is there a better way? Because cooling organs down has its problems.

“The minute you take an organ outside of the oxygenated warm environment of the donor body and put it on ice, the organ is immediately decaying,” Hassanein says. “The longer the organ stays in this environment, the higher the probability that the organ will die and it will never function when it’s transplanted.”

So ever since that first day when Hassanein put a heart in a cooler, he’s been dreaming of a new technology - one that keeps organs warm, and that keeps blood and other nutrients running through them. Hassanein says that way, you not only prevent decay, it’s possible you could improve the health of organs.

Hassanein is now the president and CEO of TransMedics, which created a new sort of device to keep donated organs warm, and alive.

There are other companies working on similar technologies. But the FDA is currently considering TransMedics technology for heart transplants, and the company is hoping to get it considered for lungs soon.

In livers, they’re just getting started with the clinical trial, which is now at four medical centers around the country. And so far the device has been used in eight transplants. One of those transplants was Lloyd Matsumoto’s.

Dr. Jim Markmann was the surgeon put that liver in Matsumoto.

“It reacted beautifully. Started making bile right away," says Markmann. He stresses this is still very new and still experimental, so it’s way too early to say whether it works better than the old and cold method, which they’ve been doing successfully for years. But he’s encouraged by what he’s seen so far.

And Matsumoto says he’s feeling great. “It was almost like a miracle. All of these things that could go wrong didn’t. And everything went right."

This coming spring, the 71-year-old is planning on teaching one more semester of introduction to biology, before going on to enjoy his retirement, and the rest of his life.

A liver. Credit: Craig LeMoult