From left: Mia Love, Barbara Comstock and Joni Ernst.

Republicans romped in the recent midterm elections, adding new lawmakers in Congress and statehouses across the country. From among those large electoral successes, GOP leaders and their allies were able to pick out a few winning women — such as Mia Love in Utah, Barbara Comstock in Virginia, and Joni Ernst in Iowa — to make a claim of a new gender diversity in the party.

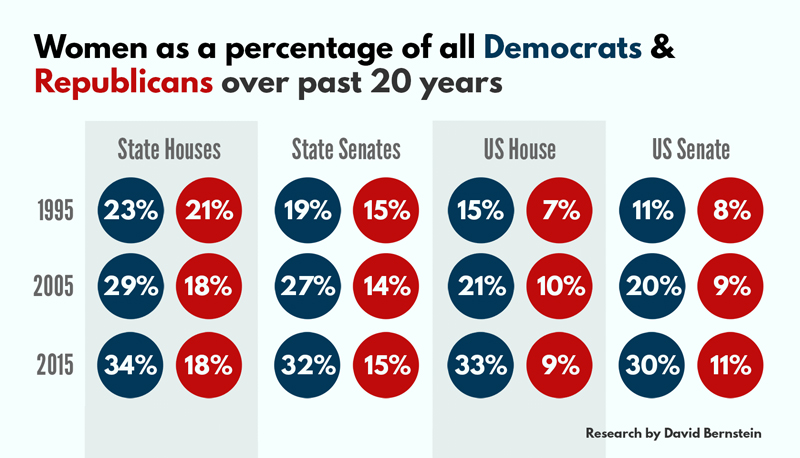

Don't be fooled: Today's Republican party is no more gender-diverse than it was 20 years ago, in the testosterone-fueled aftermath of the so-called Gingrich Revolution. The chart here shows just how stagnant the GOP has been, while the Democrats have slowly but surely added women to their ranks.

The chart above shows how the two parties have fared on gender diversity among their elected lawmakers at different levels over the past two decades.

That's the story, using the most common way of looking at the issue. Writing for the past decade about women in politics — and in particular the sharp divergence between the Democratic and Republican parties in electing women — I have tried to introduce an additional measure: the “replacement rate.” That's what I call the percentage of newly elected officeholders, in a given election cycle, who are women. While the ultimate interest lies in the rate among all current officeholders (as in the chart above), the tendency of many officeholders to stay put for years (or decades) makes that figure very slow to reflect current trends. When you start with a 90 percent male caucus, and re-elect 80 percent to 90 percent of them every year, significant change might not be evident for a long time, even if it's really taking place. The replacement rate gives a more up-to-date snapshot.

There has been significant change — not just over the past 20 years, but in the past few election cycles. After years of slow progress, Democrats are in a recent explosion toward parity (in legislative offices, at least).

Republicans appear to have stopped a recent decline in gender parity, but their replacement rates show that no growth is in sight.

Of the 45 newly elected (i.e., freshman) U.S. House Republicans in this month's midterm elections, five will be women (assuming Martha McSally survives her recount in Arizona). That's a replacement rate of just 11 percent women, and 89 percent men, for new members being added to the GOP House caucus.

The smaller freshman Democratic class, by contrast, will include 10 men and seven women (barring surprises), for a replacement rate of 41 percent women.

At the next level down, in state senate elections across the country, the pattern is repeated. Of the 178 newly elected Republican state senators, just 36 are women; a replacement rate of 20 percent women. For Democrats, the figures are 37 women out of 84, for a 44 percent women replacement rate.

(Those state senate numbers are my best attempt at careful compilation; I relied particularly on Ballotpedia, Rutgers' Center for American Women and Politics, and National Conference of State Legislatures sites, among others.)

The figures are very consistent with Republicans' replacement rates over the past two decades. For Democrats, however, this year fits in with, and even advances, the trend from the previous two cycles — which were a step up from what had been very stable replacement rates for a while.

This sharp divide in replacement rates did not exist as recently as the 1990s, and has widened considerably in just the past few election cycles, as Democrats have started electing a growing percentage of women, in good and bad election years, and Republicans haven't.

Interestingly, Democrats appear to have, at least for the moment, eliminated the traditional pyramid effect: In 2015 they will have roughly the same female composition at all (legislative) levels. I suspect that's a temporary phenomenon rather than a ceiling of some sort — especially if the replacement rates we saw this year continue.

I have some thoughts about why this is all happening, which I'll put into a separate post.