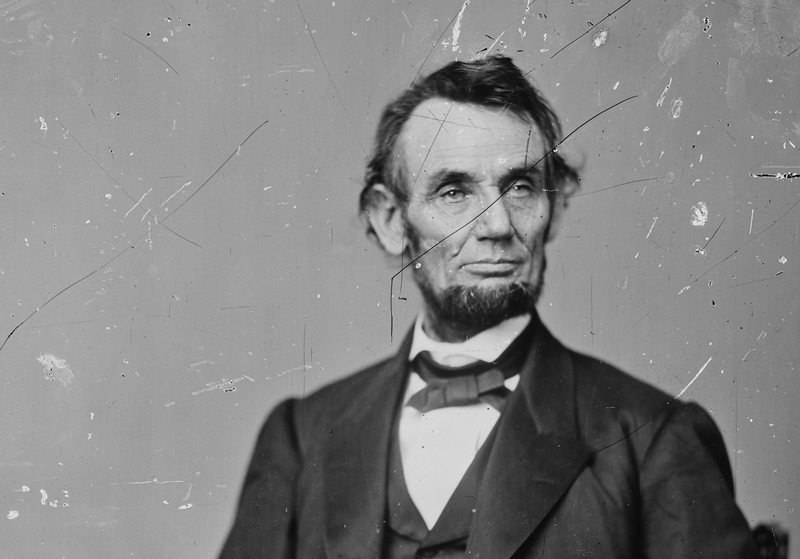

As I read Jeff Jacoby’s Boston Globe Wednesday column Who cares whether Obama is Christian? my first thought was “Republicans, of course” but then as I tried to follow Jacoby’s reasoning in defending Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, I thought of Abraham Lincoln. (As my family and friends will attest, almost everything makes me think of Lincoln).

The Washington Post had asked Governor Walker whether he thought President Obama is a Christian and Governor Walker replied that he didn’t know. From that episode Jacoby constructed a jeremiad on the unfairness of the liberal press assaulting a Republican with such an offensive question. The columnist’s logic reminded me of this excerpt from a speech Lincoln once gave in the Illinois legislature, capturing the capacity of a rival politician: “In one faculty, at least, there can be no dispute of the gentleman's superiority over me, and most other men; and that is, the faculty of entangling a subject, so that neither himself, or any other man, can find head or tail to it.”

Since Jacoby was making a larger point about whether we should care at all about a politician’s faith though I thought of a piece Lincoln wrote in 1846 after his congressional campaign, addressing the rumor that Lincoln was an “open scoffer at Christianity,” a charge Lincoln felt had damaged his vote total. Lincoln responded:

That I am not a member of any Christian Church, is true; but I have never denied the truth of the Scriptures; and I have never spoken with intentional disrespect of religion in general, or of any denomination of Christians in particular. It is true that in early life I was inclined to believe in what I understand is called the ``Doctrine of Necessity''---that is, that the human mind is impelled to action, or held in rest by some power, over which the mind itself has no control; and I have sometimes (with one, two or three, but never publicly) tried to maintain this opinion in argument. The habit of arguing thus however, I have, entirely left off for more than five years. And I add here, I have always understood this same opinion to be held by several of the Christian denominations. The foregoing, is the whole truth, briefly stated, in relation to myself, upon this subject.

I do not think I could myself, be brought to support a man for office, whom I knew to be an open enemy of, and scoffer at, religion. Leaving the higher matter of eternal consequences, between him and his Maker, I still do not think any man has the right thus to insult the feelings, and injure the morals, of the community in which he may live.

It may be that he had blasphemed Christianity. At some point he had written a pamphlet on religion but his friends deemed it such a threat to his political career that they destroyed all the copies. He might not have denied the truth of Scripture, but he doesn’t say he affirms it either, does he? Could he have spoken disrespectfully but without the proper intention – as a lawyer Lincoln would understand the different levels of intent. Then there is the Doctrine of Necessity – “that the human mind is impelled to action, or held in rest by some power, over which the mind itself has no control.” What is that power? What about the free will of man?

In Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, Allen Guelzo argues that Lincoln’s rejection of malice in favor of charity, expressed in his Second Inaugural, is a product of the belief in the Doctrine of Necessity. Lincoln did not harshly judge even the slaveholders (if we were in their position, we would do as they do) since if “the mind is impelled to action, or held in rest by some power, over which the mind itself has no control,” how can man be held ultimately responsible? Lincoln is not a passive person though, argues Guelzo. He believes his own fate is for greatness and he acts and encourages us to act “with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right.”

Lincoln also adds that he might have made arguments about the Doctrine but only among a few friends, and that not for several years. Moreover, he understands the Doctrine sounds a lot like Christianity, so what’s the harm?

Note also the politician’s careful attention to public opinion. Lincoln denies he could vote for a candidate who assails religion. No “man has the right thus to insult the feelings, and injure the morals, of the community in which he may live.”

It’s an elegantly constructed argument in which Lincoln never quite asserts his fidelity to religion. It’s about as far as that politician could go.