Here is some good advice from political science: ignore early campaign polls.

It’s an appropriate topic since polls are already being marketed on the 2016 presidential election. As political scientist Jon Bernstein recommends, Ignore Those Polls! In Why You Should Ignore the Republican Presidential Primary Polls political scientist John Sides explains that polls of general election match-ups this far out have almost no relationship to the outcome; there is no reason to think that primary polls would be any more predictive. Early polls should come with a warning label: WARNING: for entertainment purposes only.

I’ve argued this in Massachusetts before but let me draw a bit on a conference paper I'm working on. In the 2014 gubernatorial race there were nineteen polls on the Democratic primary recorded at HuffingtonPost Pollster, two (by PPP) going back to 2013. They all had Martha Coakley way ahead of Steve Grossman; up to forty-five points ahead. Polls conducted just a few days before primary day had Coakley ahead by over twenty points. She won by six. The turnout was an historical low of sixteen percent, but why go to the polls when nineteen polls tell you the race is all over?

The commercial value of being the least wrong was quickly seized by the Boston Herald, which had published a poll with Coakley leading by only twelve points about two weeks prior to the election. The Herald’s triumph is captured in this tweet by a columnist:

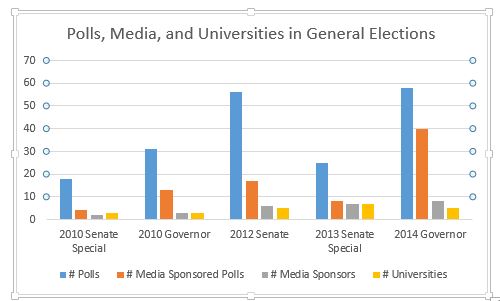

To continue with the commercial value of polls, let’s turn to the general election. This next figure is also drawn from Huffington Post for polls published in the 2010 senate special election, 2010 governor, 2012 senate, 2012 senate special, and 2014 governor races.

In the 2010 senate race only two media outlets published four of the eighteen polls while three university polling units polled. In the 2010 governor’s race the same two media outlets published thirteen of the thirty-one polls with three universities polling. In 2012 six media outlets sponsored a mere seventeen of the fifty-six polls; five universities were involved. In the 2013 senate election twenty-five polls were recorded, with eight of them media sponsored by seven different outlets, and with seven different university polling units participating.

But in 2014, eight media outlets combined to publish forty of the fifty-eight public surveys; university involvement dropped back to five institutions. The Boston Globe and the Boston Herald both polled. Two of the three of Boston’s broadcast television news stations partnered with a pollster, as did both of Boston’s major NPR affiliated public radio stations. As for the non-media affiliated polls, their business plan is to offer their polls to media outlets which then publish them, providing publicity for the pollster to attract corporate clients.

Coakley led in forty of the fifty-eight public polls of the general election recorded at Huffington Post. She led Baker in all but one of the twenty-eight polls conducted before primary day (a one point Baker lead); and in the first several polls after the primary. By mid-September the polls began to see-saw between the candidates, and by late October the polls began to shift to Baker. In other words at their core reason for being, the horse race, the polls were consistently in error until October.

“Horse race” coverage not only fulfills the needs of journalists for an interesting story, it attracts consumers. Research shows that horse race coverage is much more interesting to voters than issue or candidate biography coverage. Polls are expensive and that investment must be recovered. Yet at their core reason for being, the horse race, the polls were consistently in error until October.

Polls have assumed an oracular significance that even the best pollsters do not adequately explain to their consumers. The power of Big Data allows pollsters to command the high ground. As Professor Thomas Patterson says, the scientific basis of polls aid journalists by appearing to serve the value of objective knowledge. In Amusing Ourselves to Death Neil Postman wrote of “the equation we moderns make of truth and quantification. In this prejudice, we come astonishingly close to the mystical beliefs of Pythagoras and his followers who attempted to submit all of life to the sovereignty of numbers.”

Do we need fifty-eight polls in a year, or eight in a week, or several the same day? A Vanishing Voter Project study following the 2000 presidential campaign found that two-thirds of Americans agreed that campaigns “seem like theater or entertainment rather than something to be taken seriously.” Poll proliferation exacerbates that problem.

In a couple of weeks I’ll be presenting a paper on the 2014 Massachusetts election at the New England Political Science Association annual meeting. I’ll cover what I see as entertainment through polling; debates that are more low farce than high stakes; and the dislocation of trust in our advertisement driven “conversation” about politics. Your comments will help me improve the paper.